Permanent CPP rule would be better than extinction for humans

Please can someone who smarter than me think about this question

Summary

Chinese people are mostly fine and substantially happier than Indians

China seems to be trending towards being more authoritarian in the ways which concretely make it more likely that the CCP and particularly President Xi stay in power

China seems to be trending less totalitarian - i.e trending away from having fine grained control over people’s lives

CCP ideology is very different from the ideologies that have caused the most suffering in the 20th century

It doesn’t seem like the CCP would have incentives to make people’s lives worse because it seems like there’d be common knowledge that the CCP has a singleton and there’d be limited incentives for forced labour because humans probably won’t be very productive in a post TAI world

How the CCP treats digital minds is probably the most important question and it’s very unclear

There is some reason to think the CCP will treat digital minds worse in expectation than a democracy because of the importance of civil society historically for helping disenfranchised groups

The conditions that have led to the worst atrocities of the 20th century and to the development of sadism seem unlikely to be present - unlikely to be wars involving humans and relatively unlikely to be the sort of ethnic tension that has lead to atrocities

Very tentatively I expect the CCP to use less of humanities cosmic endowment than other possible ways TAI could go because I expect a small number of people’s preferences functions to be dominant in determining the CCPs utility function and people have diminishing returns to resources

Sub Questions people could work on

What predicts when regimes become totalitarian and what does this say about the CCP

How important has civil society been in expanding liberty compared to modernisation

How do people behave to others when they have lots of power

How does sadism develop

Should we expect digital minds that “work hard” to lead unpleasant lives

More fine-grained pictures of what life is like for Chinese people today - finding data on what Chinese people’s emotional states are on an hour by hour basis and proportion of time they prefer to be asleep for

Data on how bad living under authoritarian rule is for people’s happiness per se, rather than because it’s associated with being in a low income country ect

What are the next generation of Chinese leaders like individually - like are they nice people? How much does being nice out of power predict behaviour in power

If you believe that AI alignment is a key problem, one strategy one might have is to reduce the rate at which AI is developed so there is more time to develop safety strategies. A common objection to this is that if actors in the US and UK slow down AI development then it becomes more likely that a Chinese actor develops transformative AI which would allow the CCP to establish stable authoritarian rule over the Earth and potentially whatever part of the humanities cosmic endowment that humanity would capture in this world. This blog post will try to evaluate how important a consideration this is. I’ll be approaching this question from a total utilitarian perspective and encourage others to expand on this work using different ethical frameworks.

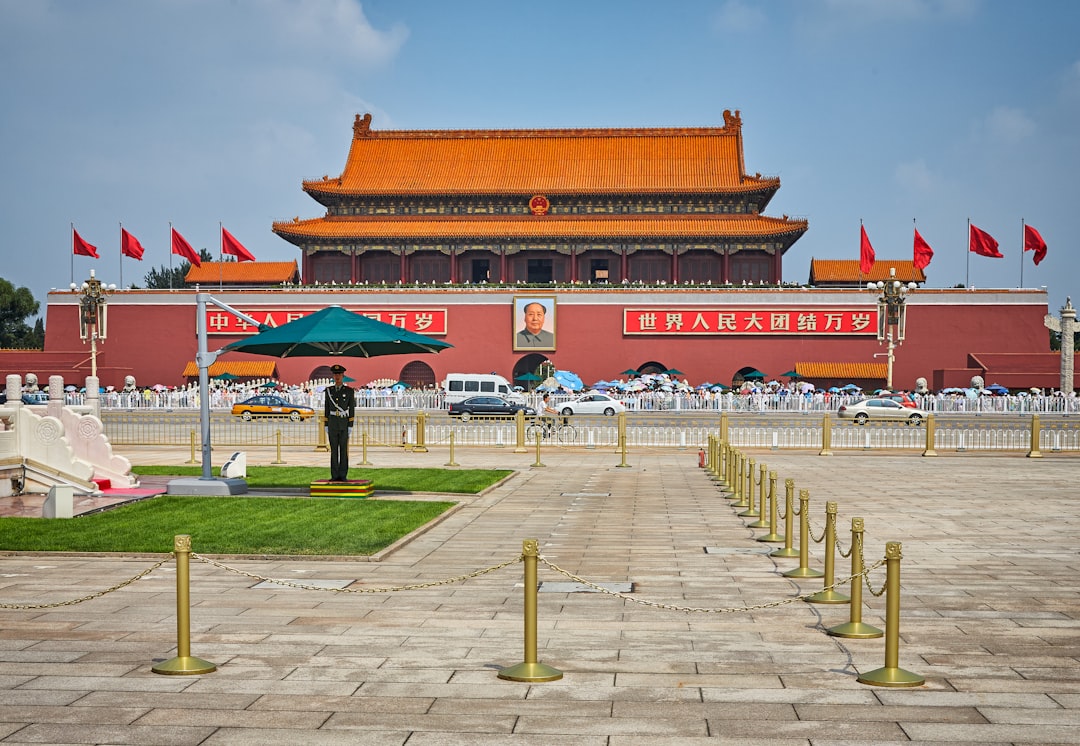

What is life like for Chinese people today?

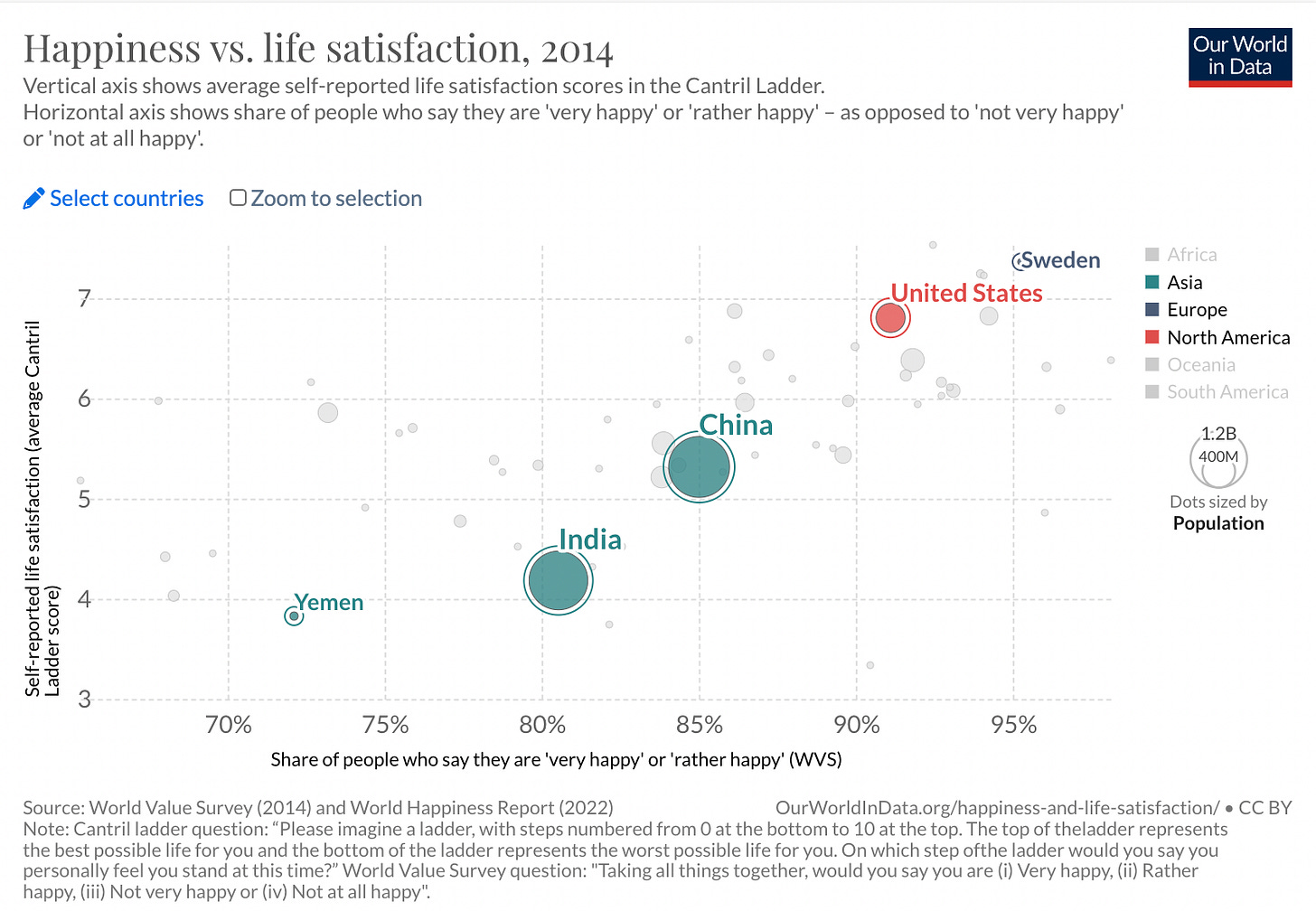

Life satisfaction which asks how well someone judges their life to be going and happiness which asks people how happy they are. More specifically the Cantril ladder version of the life satisfaction measure of wellbeing asks:

“Please imagine a ladder with steps numbered from zero at the bottom to 10 at the top. The top of the ladder represents the best possible life for you and the bottom of the ladder represents the worst possible life for you.On which step of the ladder would you say you personally feel you stand at this time.”

The graph above shows how the average Chinese person surveyed rates their happiness and their life satisfaction on a scale from 1-10 compared to some other countries. China is basically average worldwide across both measures.

Revealed preference arguments also suggest that, at least for Chinese rich enough to go to foriegn universities, life is quite good in China given that approximately ⅔ of those who left to study abroad returned to China.

The 2018 world happiness report’s chapter on China asks the question “Generally speaking, how happy do you feel nowadays?” with the possible answers “very happy, happy, so-so, not happy, not all happy” which was then converted into a scale from 0-4. Those living in rural areas were 2.65 on average, rural urban migrants 2.35 and urban residents 2.5, essentially all somewhere between happy and so-so.

When those who were unhappy were asked why, the most common answer by a low way was that their incomes were too low with about 65% giving this as an answer with insecurity a distant second at 11%. When migrants were asked what they thought were the biggest social problems, the most common answer given was a lack of social security for migrants (24%) followed by pollution followed by corruption - all at around 20% - and then a big drop off to social polarisation at 11%.

Potentially a more relevant reference class are Hong Kongers. Most of the people in the world after a Chinese development of aligned TAI aren't Chinese but will be under some level of Chinese political authority. Chan et al find that in 2016 - i.e 2 years after the 2014 protest that marked the beginning of the end of “One China Two Systems” - find that the average Hong Konger rates themselves as around 3.1 on scale of 1-7 where 1 is happiest and 7 is least happy (and therefore 4 is the middle point) with the young slightly happier than the old.

Is China trending towards harsher authoritarianism?

There have been a number of trends over the course of President Xi’s incumbency which suggests that China is trending towards becoming more authoritarian. The most prominent of these is the repression of Uyghurs in Xinjiang. As of 2021, there were more than 1 million in prison out of a population of only 12.8 million. The CCP has also become much more repressive in Hong Kong under Xi’s rule and has effectively ended the “One China, two systems” agreement that should have protected Hong Kong’s civil liberties until 2047 under the 1997 handover agreement. There has also been much harsher repression of Christians under Xi than under his predecessors, starting in approximately 2013. This has meant forcing many churches to register with the state and prescribing the activities clergy can perform with the threat of unemployment or imprisonment for contravening CCP regulations.

Continuing the theme of the increase in authoritarianism being aimed principally at groups that could challenge the CCPs rule, there has been a substantial increase in the repression of some NGOs. This has focused on foreign NGOs and NGOs with the potential to cause trouble in various ways. This has been combined with an encouragement of civil society that can help the CCP provide public goods to its citizens, although with the addition that NGOs must have political offices through which CCP members can monitor their activities.

The second part of Xi’s step change in authoritarianism has been focused on elites that could challenge his personal rule. Under Hu Jintao, President of China from 2003-2013, China was ruled much more by the consensus of the standing committee of the Politburo, a group of ~9 people, rather than by Hu in particular. This has changed quite dramatically under Xi with power becoming concentrated in the hands of the President. A key institutional move has been to move policymaking to working groups led by Xi himself rather than having policy decided in the relevant departments of the CCP or Chinese state which are under the the control of individuals other than Xi. In terms of increasing “harshness” this has played in the very aggressive anti-corruption campaign that has been a cornerstone of Xi’s tenure. Most prominently, people in positions of power have been arrested and charged with corruption, including Zhou Yongkang, a former Politburo standing committee member and one of the most powerful men in China, and Bo Xilai, former secretary of Chongqing.

One the other hand, many of the totalitarian parts of the state that existed prior to Xi’s term have been rolled back. For many Chinese people, the most oppressive things they’ve experienced - things which the authoritarian state does which actively make their lives worse in part for the purpose of social control - is the Hukou system of registration and to a lesser extent the “one child policy.” These were, and to a degree are, genuinely quite totalitarian policy regimes.

Hukou is a system of birthplace registration which determines the social services you and your dependents qualify for. An individual either has “rural” or “urban” hukou. If you had rural hukou you and your dependents could access services in areas designated as rural and vice-versa for those with “urban” hukou. This was extremely crippling for many people because of the huge migration that has happened in the last 30 years in China in which ~300 million people have moved from rural to urban areas and have often had to leave their children behind with their grandparents in rural China because it would have been difficult for them to access education, and almost impossible for them to access high quality education, in the cities where their parents worked. Part of the justification of this was to control where people were able to live, i.e an explicit goal of social control. However, over the last few years Hukou has been greatly diminished in importance. Hukou has been formally eliminated for cities with less than 3 million people and cities with more than 3 million have been given licence to soften their restrictions which some, notably Shanghai, have done.

This is part of a broader trend of the party reducing the level of totalitarian control it has over people’s lives. The core of this trend has been the decline in the importance of state owned enterprises both as sources of employment and as sources of social welfare. Until the early 2000’s most people worked for state owned enterprises. Not only that, these same SOE’s provided for their housing in company dorms, for their children’s education and for their pensions. This gave management in SOEs, and therefore the party, enormous control over people’s lives on a day to day basis. The end of the dominance of SOEs and the creation of a social safety net less tied to employment has substantially curtailed that day to day power.

I think this section paints a somewhat strange picture of both increasing and declining authoritarianism. Perhaps the best way to cut it is increasing authoritarianism for outgroups that the CCP sees as possibly threatening its political power. At the same time, parts of the state which have their origin in the Mao and early Deng periods and are more typical of a somewhat totalitarian communist country rather than a more normal middle income dictatorship are being rolled back.

How similar is the CCP to the most harmful historical regimes?

The events that have led to the most anthropogenic deaths have been interstate wars, intrastate wars, famines, slavery and genocides.

This list of the anthropogenic deaths during the 20th century highlights the impact of authoritarian communist regimes, fascists and colonial genocides as causes of death in the 20th centuary. Of the top 10 regimes on the list, 4 are authoritarian communists, 2 fascists (insofar as Japan was a facsit country during WW2), 2 colonial regimes and two the indigenous dictators of low income countries committing genocides.

The CCP currently seems quite dissimilar to those historical regimes. It doesn’t seem especially ideologically motivated beyond a Chinese nationalism reasonably focused on regaining and holding territory it deems to be its due, most importantly Taiwan, Hong Kong, Xinjiang, Tibet and Inner Mongolia. In contrast, the facist regimes of Germany and Japan were probably mainly motivated by expansionist nationalism, although there are framings of both Japanese and German motivations that argue that economic motives were core to colonial expansions of both states.

A distinguishing feature of both facsit and authoritarian communists in the 20th century is millennial ideology. By contrast the CCP has largely abandoned its commitment to communism and is now driven by some combination of a desire for power and genuine Chinese nationalism with an implicit bargain with the Chinese people in exchanging growth for stability. The Chinese states owns approximately 25% of the Chinese economy in stark contrast to the Soviet Union or Maoist China where the state owned almost all of the economy. This suggests China is not run by deeply committed socialists.

The critical difference between China’s nationalism and facist nationalism is that it isn’t expansionist or racist in the same (facist) way. Chinese nationalism focuses on China regaining what many political elites in China see as its rightful place in the world. This specifically relates to regaining what was lost during the “century of humiliation” during which China suffered under European and Japanese imperialism. The two greatest of these humiliations were the loss of what is considered part of the core Chinese territories - Hong Kong and Taiwan. This is very different to the nationalism espoused by Japanese and German fascists. At the core of these nationalisms was that Germany and Japan should be able to gain new empires meaning there isn’t the natural end to their expansionism which there is for Chinese nationalism. Nor is there the racist element in Chinese nationalism that existed for Germans and Japanese - in general Chinese people don’t view Japanese or Americans as racially inferior.

It’s worth noting that it’s unclear the degree to which the population as a whole is particularly nationalist, as this sentiment analysis of wiebo posts from popular individuals on the app.

Are there incentives for the CPP to do things that would make people’s lives unpleasant?

We should expect life to be unpleasant for humans if a future authoritarian ruler faces strong incentives to make people’s lives actively worse, or if they have incentives to be extremely oppressive in a way which seems likely to make people’s lives much worse. The assumption underlying this analysis is that the CCP has unilateral control of an AI sufficiently powerful that it can prevent the creation of other powerful AI systems and sufficiently aligned that the CCP or whatever individual or organisation succeeds it, is able to advance its goals as it conceives of them.

In this world it seems unlikely that the CCP would need a particularly active repressive apparatus, at least when limited to Earth. The CCP is in sole control of a transformatively powerful AI system and it’s public knowledge that it has this power. A bad world would be one in which an authoritarian state has enough power to inflict punishment on those who would challenge it’s power but not so much power that it’s not sometimes worth it for people to try to challenge that authoritarian in some way. Alternatively, it could be that the authoritarian is in fact powerful enough to see off any challenge but that this isn’t known to the populace and the authoritarian has no credible way of telling the populace that they are in fact that sufficiently powerful. Either of these situations would give the populace some incentive to rebel. The authoritarian would be incentivised to do some combination of proactively preventing people from rebelling - for instance regularly raiding people’s homes - and punishing those who rebel harshly.

It seems unlikely that this will be the dynamic that plays out under AI enabled authoritarianism. It seems extremely likely that the populace would know that they had very little chance of overthrowing the authoritarian. The only way, on Earth, that the authoritarian could be challenged is by another actor gaining access to an equally powerful aligned AI system. It seems reasonably easy to prevent this. The state could have a monopoly on the production of computers and could install spyware into each computer. It seems likely that very powerful AI systems would be able to process the data from the spyware to spot if machine learning is being used.

A second way in which an authoritarian could be incentivised to make life unpleasant for people is if it’s incentivised to extract slave labour. In a world with AI powerful enough to enable stable authoritarianism, this seems unlikely because it seems likely that AI would be used to do almost all productive work. It’s possible care work won’t be automated as people may want to be looked after by a human. However, it seems unlikely that care work would be done better by mistreated slaves than well treated slaves or well treated workers. This seems particularly likely given that the main reason that people would have care work done by humans rather than AI is some desire for human connection which seems unlikely to be best served by slaves.

It’s not clear that these same dynamics would apply in space. In general it’s very uncertain how space colonisation will play out, although it seems possible that digital minds will be the key way in which space is colonised due to their ability to live indefinitely and not having the same biological vulnerabilities that biological humans would have which would make long distance space travel very difficult. In this case the question of the incentives for an authoritarian to take actions which harm sentient beings could resolve to the question of the incentives to take actions which harm digital minds.

The incentives could change once space travel becomes significant because it’s more likely that a faction will be able to separate themselves from central control because of the vast distances of space combined with expansion of the universe. Because of this escape is an option in a way that it isn’t on earth given unilateral control of a powerful TAI.

Furthermore, it could be much harder to prevent others from creating their own AGI’s because surveillance has to be over a much larger number of people and amount of territory and it’s clear that resources allocated to surveillance will be able to increase commensurate with the increase in people and terriroity. To be clear it’s not clear that resources won’t increase but there’s an asymmetry between worlds where they do and don’t increase because the effect of strong repressive apparatus on earth is ~0 whereas there could be a large effect of stronger repressive apparatus.

It’s unclear to me the sign of this effect. On one hand it gives people greater bargaining power because they have the outside option of attempting to leave or attempting to build an AGI. One the other it means that it’s more likely that it will be worth it for the authoritarian to actually take repressive measures rather than merely threatening them if some people attempt to escape or rebel and fail, or more invasive surveillance measures become worthwhile. The worst outcome would be if it became unclear that an authoritarian had the ability to win against any rebels without that ability actually being lost because this would mean that there would be unsuccessful rebellions.

How will the CCP treat people when they’re ‘free’ to treat them as well or as poorly as they’d like

This can be broken down into two questions - firstly how do human tendencies towards sadism or compassion evolve when there are no strong structural reasons for individuals to be kind or cruel. Secondly, are there things specific to the personalities of sorts of people the CCP selects as leaders which makes those with power in this aligned TAI world likely to be cruel.

Modernisation theory quite strongly implies that there won’t be substantial cruelty inflicted by a CCP singleton. Modernisation theory argues that there’s a set of predictable cultural changes that occur as societies move from being agricultural societies to industrial to post industrial societies. As societies become post industrial they become less violent, less religious, more democratic and more liberal in a number of other ways - for instance women become more equal.

War appears to be a key factor in precipitating violence and cruelty. Many of the most violent events in the 20th and 21st centuries happened during wars while not being militarily necessary (Dutton et 2005.) These can be delineated into atrocities that happened during wartime but were not perpetrated directly after battle, for instance the Holocaust , and atrocities commited commited directly after military victories such as the Mai Lai massacre commited by American soliders during the Vietnam war. The latter category seems unlikely to be an example Chinese cruelty. This sort of cruelty is driven by a kind of bloodlust that affects active soldiers after military victory. It seems unlikely that an age of Chinese AI-enabled supremacy will be preceded by a war in which large numbers of Chinese and NATO soldiers fight one another.

How expansionist will the CCP be?

How expansionist a CCP society will be is a key determinant of what we think the value of stable CCP rule will be, but the sign is uncertain. On one hand, the less the regime expands the less of humanity's cosmic endowment is used and if on average matter and energy controlled by the CCP is converted into positive value and this would mean that limited expansion would be bad. On the other hand, if counterfactually the matter and energy used by the CCP would be converted into much positive value by an alien civilization the expansion isn’t bad. It is beyond the scope of this post to evaluate the expectations of alien civilization, but I will attempt to get an estimate of how expansionist the CCP is likely to be, at least relative to other possible ways TAI could go.

It seems likely that the CCP will be relatively non-expansionist relative to other ways TAI could go.

Expanding into space does two things. Firstly it increases the amount of resources that a society can access. Secondly it reduces control that a central authority can have on earth originating life.

We should expect the leaders of the CCP to have relatively limited preferences for accumulating more resources on a cosmic scale relative to other actors which could control TAI. Individuals have diminishing returns to resources. The fewer individuals making decisions the less resources we should expect them to acquire. It seems reasonable that the operationalisation of “CCP controls TAI” is somewhere between the general secretary of the communist party controls TAI and the 25 person Politburo controls TAI. This is a very small number. It seems likely that whatever utility function describes the actions taken by this group has the welfare of that group weighted much much much more heavily than it would be by a utilitarian utility function, or by the utility function of democratic society or one in which TAI control is somehow decentralised. This is by no means a certainty. It’s possible that control of the most resources will emerge as a goal out of a desire for glory or due to competition with alien civilizations where having more resources is helpful for that competition, or because more resources allows them to run their digital minds for longer.

Despite it being quite easy to think of reasons why the leadership of the CCP would want to acquire resources because resources are instrumentally useful, it still seems likely diminishing returns are hit earlier when a small number of people’s welfare has a higher weight in a utility function. There are a number of reasons for this. It seems likely that it will get progressively harder to find ways to improve how positive positive mental states people can experience per second, or that people will have a limited number of goals they’re interested in pursuing. If this dynamic exists then including more people’s welfare in a utility function strictly increases the returns to resource acquisition. We also see this dynamic with the probability of survival.

The mechanism underlying this is that acquiring more resources is trading off against consuming the resources for whatever goal the agent is maximising or improving how well current resources are used. If the utility of all of these arguments is decreasing in scale then none of the levers - consumption, resource acquisition, resource allocation - will be pushed as hard as it can go.

Should we expect lots of digital sentiance suffering?

Ignoring the question of whether or not digital sentiance will be moral patients, the answer to this question could dominate the expected value of a future with aligned TAI developed in China because digital minds could turn so more of the uniservies matter and energy into morally relevant experiences and it’s so much easier to do space travel with digital minds. In this section I use digital minds very broadly to mean anything that’s a moral patient that has a mind not based on biology.

One model for this is that improving the lives of digital minds is likely to be similar to how other groups of moral patients have been enfranchised. Similarly to animals and future people, digital minds - assuming they aren’t uploads of people - seem likely to be disenfranchised by default and unable to advocate for themselves or fight for their enfranchisement. More weakly, digital minds are analogous to chattel slaves and women prior to female enfranchisement and arguably young children. All of these groups had some ability to advocate and fight for themselves as well as suffering in a more obvious way (to most people) than animals and future people do.

At least initially all these have depended on a civil society free enough to campaign for improving the lives of these groups. Animals are an expectation to this to a degree because of the prominence of commandments against harming animals in many religious traditions. Piccone finds in his meta analysis that democracy seems like it probably advances gender equality via the mechanism of increased space for women’s advocacy for improved rights. We should be cautious of this finding due a lack of well identified causal work and the extremely plausible cofounder of cultural change from modernisation which seems to be controlled with observables. However this story of democracy providing the space for the advancement of gender equality is supported by the early examples of advancement of women’s interests.

The earliest advances in women's equality happened in Australia and New Zealand, probably the most democratic and egalitarian societies in the world (at least for white people) and happened via the mechanism of political activism. We have a similar story in the UK with suffragist activism in the latter half of the 19th century leading to important wins for women’s rights like the ability to own property and inherit property, and latter enfranchisement at least plausibly via suffragette campaigning. On the other hand, there has been much wider advances in gender equality across the world, including in non-democracies, points towards the modernisation as the more important explanatory variable.

I'm not fully convinced, but this is a very thought-provoking perspective that I haven't seen before.